Have you ever heard the objection, “Oh yeah? But who made God?” The answer, of course, is that nobody made God, but this has still been a stumbling block to a lot of people, so let’s work through that today.

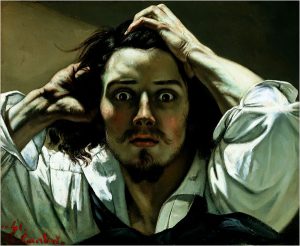

Let’s start by looking at this question as famed atheist Bertrand Russell posed it in 1927 in his “Why I Am Not a Christian” speech. Next week, we’ll take a look at Richard Dawkins’ recycling of the question in 2006. First, let’s hear from Russell, considered by some to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, in his own words:

“I for a long time accepted the argument of the First Cause, until one day, at the age of eighteen, I read John Stuart Mill’s Autobiography, and I there found this sentence: ‘My father taught me that the question, “Who made me?” cannot be answered, since it immediately suggests the further question, “Who made God?” ’ That very simple sentence showed me, as I still think, the fallacy in the argument of the First Cause. If everything must have a cause, then God must have a cause. If there can be anything without a cause, it may just as well be the world as God, so that there cannot be any validity in that argument.”[1]

To speak of God (at least, in the Christian understanding of the title) as needing a cause, is to speak irrationally. That is like asking “Who moved this unmovable object?” Or ” When did this beginningless entity begin to exist?” If the terms are correctly understood, they are understood to be contradictory and the question invalid. For part of being “God” is being eternal and possessing necessary existence (i.e. He always existed, and He has to exist for anything else to exist). If you’re thinking of any entity that could be “made”, you’re simply not thinking of God.

Consider the following scenario. A clever young man gets an idea for a truly useful gadget that everyone will want. He starts making them in his garage, but quickly outgrows that, and soon he is forming a company and building a factory. More hiring, more expanding, and soon the company has grown and has to have several layers of management at multiple factories. Now several years after that humble beginning in a garage, Billy, a new worker at the newest factory is going through employee training. He learns who will be his Line Foreman, and Shift Supervisor, and Department Manager, on up the chain of command until finally, it stops at President and Owner. Now, young Billy raises his hand, and asks, “Who’s his boss?” Nobody… he’s the owner,” comes the answer. But Billy persists, “Yeah, but who appointed him owner?” The trainer responds, “Nobody appointed him owner; he’s the original owner… he founded the company. It wouldn’t even exist without him.”

Now, was the company trainer trying to trick Billy when he said nobody needed to appoint John as president because he founded the company? No, of course not. Founding a company necessarily means you exist before the company you found. But what if the “company” is, instead, all of reality? And the founder is God? His pre-existence means there can be no other entity around to appoint Him or “make” Him, and this stops the infinite regress of the causal chain that concerned Russell.

The fact that people ask “Who made God?” is actually a testament to the self-evident nature of the law of causality; we instinctively recognize the relation of cause and effect and look for it everywhere. But this also demonstrates the common misunderstanding of it that Russell also fell prey to: people tend to think that this principle states that every effect has a cause. If that really were the case, then “Who made God?” might be a legitimate question. But here’s the problem: it’s a sloppy sentence – a shortcut that doesn’t always work. While we can be intellectually sloppy like that in our day-to-day observations, applying any statement universally requires more intellectual rigor. To correct the statement, we need to say, “everything that begins to exist has a cause.” Something without beginning would not require a cause, nor could it have a cause. Russell does acknowledge this as a possibility in the last sentence quoted above, but then assumes that the eternality of the physical world (or universe) is just as adequate an explanation as God, which is his second mistake.

Most people can be excused for thinking “everything must have a cause” because everything we observe did begin to exist at some point, so the shorter wording appears to apply universally; but a philosopher of his stature should not be caught by such careless wording. Granted, he fell for this when he was young, learning it from an author he respected, but to continue to believe that confirms something observed elsewhere about the skeptic: though portrayed as intellectual rejection of God, their reasons are very often emotional or volitional instead [2]. The tragedy here is that John Stuart Mill would come to such a bad conclusion, not seek out a better explanation, promulgate his error, and that it would be picked up by someone like Russell and passed on to succeeding generations. Folks, I don’t mind if you question Christianity, and you’re certainly not going to come up with a question that’s going to stump God; so by all means, test everything and hold on to what’s good, as Paul would say [1Thes 5:21]. But don’t forget to question your skepticism too.

[1] Bertrand Russell, “Why I Am Not A Christian”, speech delivered 3/6/1927 at Battersea Town Hall, England.

[2] J. Warner Wallace, Cold Case Christianity, (Colorado Springs: David C Cook, 2013), p. 132. Also online here.