For this 2nd anniversary of my blog here, I wanted to take some time to explain what a “well-designed faith” is. It is, of course, this blog: this exhausting labor of love dedicated to helping fellow Christians and skeptics alike to see the beautiful, reasonable truth of Christianity. It’s where I do my best to answer objections to Christian beliefs, explain misunderstood doctrines, encourage clear thinking through the application of logic and sound philosophy, give an engineer’s perspective on God and the Christian faith, and hopefully give those who have rejected Christianity in the past reason to take a second look. It is an endeavor that, if it were followed and read by millions, but nobody came to accept the truth of God’s Word through it, would amount to nothing but a supreme waste of time. But on the other hand, if I get to Heaven, and the one person that had read my ramblings says, “Thank you. God used your words to point me back to Him,” all the hours spent here will be justified. But beyond the blog itself, a “well-designed faith” is also the focus of the blog. For I do believe that “well-designed” aptly describes the Christian faith.

For this 2nd anniversary of my blog here, I wanted to take some time to explain what a “well-designed faith” is. It is, of course, this blog: this exhausting labor of love dedicated to helping fellow Christians and skeptics alike to see the beautiful, reasonable truth of Christianity. It’s where I do my best to answer objections to Christian beliefs, explain misunderstood doctrines, encourage clear thinking through the application of logic and sound philosophy, give an engineer’s perspective on God and the Christian faith, and hopefully give those who have rejected Christianity in the past reason to take a second look. It is an endeavor that, if it were followed and read by millions, but nobody came to accept the truth of God’s Word through it, would amount to nothing but a supreme waste of time. But on the other hand, if I get to Heaven, and the one person that had read my ramblings says, “Thank you. God used your words to point me back to Him,” all the hours spent here will be justified. But beyond the blog itself, a “well-designed faith” is also the focus of the blog. For I do believe that “well-designed” aptly describes the Christian faith.

Hebrews 11 is often called the “faith chapter” or the “faith hall of fame” of the Bible because it defines faith, and gives many examples of it lived out in Jewish history. Verses 9-10 tell us about Abraham, and say that “by faith he lived as an alien in the land of promise, as in a foreign land, dwelling in tents with Isaac and Jacob, fellow heirs of the same promise; for he was looking for the city which has foundations, whose architect and builder is God.” That last description of God as an architect and builder has always caught my eye. Shortly after that, Hebrews 12:2 tells us to fix our eyes on Jesus, “the author and perfecter of faith“.

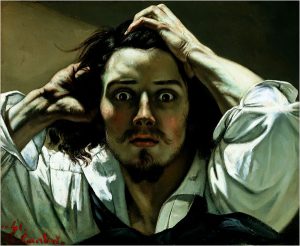

When the Bible tells us that Abraham was faithfully seeking that city “whose architect and builder is God”, it’s telling us about the long-term plan that God has held for all eternity, the goal that He both selected before the creation of the universe, and works to actualize across human history. When it states that Jesus is the author and perfecter of faith, it is saying that He perfects – completes – the trust, (or faith) birthed in us by God.[2] In fact, this word “perfecter” is the Greek word τελειωτὴν (teleiōtēn), meaning a consummator, one bringing a process to its finish. Digging deeper, this is based on the Greek root “telos”, which denotes the end goal of something. This is the root of our modern word teleological, meaning “to show evidence of design or purpose.”[1] That’s why the argument for God from observed design in nature is called the “teleological argument“. How does this perfecting of faith work? Maybe similarly to how we see design work in the building industry I’m a part of.

My profession of engineering is often lumped in with 2 other related fields to form the industry grouping AEC: Architecture, Engineering, & Construction. And these generally go together well as we’re constantly working together to complete a finished project. The architect is designing the building to meet certain goals of the client, whether it be a hospital, school, business, or a residence. The hospital needs to contain a certain number of beds, lab equipment, operating and exam rooms, and offices to accomplish their goal of caring for the sick. The school needs to have a certain mix of classrooms, teaching labs, music rooms, and sports areas, to accomplish their goal of providing a well-rounded education. A business may need flexible floor plans that can be changed as the business changes and grows. Some businesses even have essential specialty equipment that the building has to be constructed around. Even a home is going to have very different needs to accommodate one family versus another. Different home designs might focus on things like handicapped access to all the rooms, natural ventilation in the tropics, heating efficiency in the far north, “safe rooms” in America’s Tornado Alley, and so on. But in all of these examples, there is one thing in common – an end goal, a purpose. That goal drives the design. It’s counterproductive for an architect to design an amazing sports stadium for a music school that doesn’t even have a sports program!

As engineers, we work to ensure the architect’s vision of the client’s goals is actually achievable. We complete, or perfect, that initial design, by putting bones to the flesh, so to speak. We execute specific selections to make the architect’s idea buildable. The laws of physics can be brutally unforgiving, and sometimes we have to be creative to ensure the architect’s “bold vision” holds up in real life. There’s a lot of coordination there as architects and engineers work together to make choices that accomplish the client’s purpose while conforming to real-life constraints. But finally, the plan is complete and the builders come in and turn the client’s dream, the architect’s vision, and our calculations into an actual, usable building.

It seems like there is a similar spiritual workflow as:

- God the Father initiates a plan for us, drawing us to Him,

- God the Son completes the plan and accomplishes tasks (like the atonement) needed to make it happen, and

- God the Holy Spirit develops it in us through His work of sanctification in our lives.

Initiation, execution, and development working seamlessly together in the perfect unity of the triune Godhead to conform us to His image, that we might fulfill our purpose and glorify God – that is a most well-designed faith, if you ask me!

[1] https://www.wordnik.com/words/teleological, accessed 2016/09/08.

[2] John 6:44, NASB. As Barnes says in his commentary on this verse: “In the conversion of the sinner God enlightens the mind (John 6:45), he inclines the will (Psalm 110:3), and he influences the soul by motives, by just views of his law, by his love, his commands, and his threatenings; by a desire of happiness, and a consciousness of danger; by the Holy Spirit applying truth to the mind, and urging him to yield himself to the Saviour. So that, while God inclines him, and will have all the glory, man yields without compulsion; the obstacles are removed, and he becomes a willing servant of God.”

S.D.G.