On April 19, 1995, a truck bomb was detonated in front of the Alfred P Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. While it was an incredibly powerful bomb that did extensive damage to hundreds of buildings in a 16-block radius, there is one primary reason for the devastating partial collapse of the Murrah building. The front of the building, where the bomb was detonated, used what’s called transfer girders on the 3rd floor to support the columns for the upper six floors. They worked great for creating a more open entrance with ground-floor columns spaced at twice the distance of the columns on the 8 stories above, but they also decreased the number of load paths available for supporting the weight of the floors above. Therefore, when the truck bomb was detonated right next to a ground-floor column, shattering it and shearing through the columns on each side of it, 8 of the 10 bays of the building’s north facade were now unsupported. From the 3rd floor up, taking away that much support would’ve required eliminating 7 columns, but at the first 2 levels, it only took the destruction of 3 columns. This was a painful reminder that part of making a resilient building that can survive disasters is having redundancy, the ability to safely redistribute loads through alternate paths in the event of the loss of one load path. It’s what a lot of us engineers like to call a “belt and suspenders” design. As a Christian engineer, I have to ask, is my belief in God such that one crisis of doubt will destroy it, or is it more robust than that? I think you know the answer, but let’s work through that today.

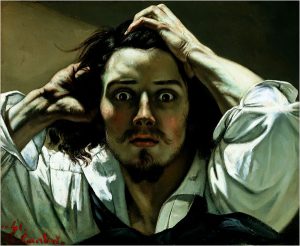

In reading atheists’ stories of their deconversions from the Christian faith they had grown up espousing, I am struck by how precarious their trust (or faith) seems to have been. Atheists like Bart Ehrman, Dan Barker, and Matt Dillahunty have told of surprisingly small things making shipwreck of their souls. Whether it’s built on a particular emotional experience, or the teachings of a particular church or pastor, or some very shallow understanding of the Bible, they seem to often have a belief structure resembling a house of cards. Frustration with the hiddenness of God, a personal encounter with suffering, inability to fathom their omniscient Creator’s reasons – and the cards come tumbling down. Yet Christianity is anything but a house of cards. The basic belief in God is not built on one make-or-break proposition. Rather, we have a strong cumulative case based on multiple lines of reasoning. Most well-known among these are the Cosmological Argument, the Design Argument, the Moral Argument, and the Ontological Argument, although arguments from consciousness, miracles, religious experiences, beauty, and reason [1], just to name a few, have also been developed over the years in support of the existence of God. Different people often find particular lines of reasoning among these especially persuasive, and others not so much, hence my use of the term “argument” rather than “proof”. Proof can be very subjective, as anyone that’s ever had to sit through jury deliberations can confirm. But what’s fascinating is how many different supports there are for rational belief in God. Of course, like the many columns in a building, no single argument supports the entire “structure” of belief in God, but all of these different lines of reasoning, taken together, interlock well to provide a formidable framework highly resistant to collapse. While skeptics often seem to enjoy sniping at the views of others, the significant challenge for the skeptic is formulating a worldview of their own that explains so much of the world around us as well as Christianity does.

“But”, one might say, “you’re doing a bait-and-switch between the case for generic theism and the case for Christianity! Christianity has all its eggs in one basket – the Bible. So much for your redundancy!” Here’s the thing: while the Bible is conveniently bound in a single volume now, the writings contained therein were the result of multiple witnesses writing independently at different times and places. Though all inspired by God, they are separate historical records. And everything described in the Bible that has ever been able to be compared against archaeological findings has confirmed the truthfulness of the Bible. In particular, Luke, Paul’s companion and the author of the gospel according to Luke and the Acts of the Apostles, has been proven to be a historian accurate in even the most trivial details. So Christianity encompasses the general case for theism, with its strong philosophical support along several independent lines, as well as having strong historical attestation and archaeological support. In fact, I would say Christianity is the only system that answers so many questions coherently and is so well-grounded.

Now, for the Christian, our trust in Christ isn’t simply a matter of intellectual assent, but also a relationship with our living Creator. The Bible tells us that the Holy Spirit, the third person of the Trinity, dwells in each Christian, and testifies with our spirit that we are children of God [Ro 8:16]. This should be the single biggest contributor to an unshakeable faith, but we humans are often fickle creatures, prone to worry and doubt, falling far short of what God intends for us. To make matters worse, false religions have claimed similar certainty, such as the Mormon “burning in the bosom” that they genuinely believe to be authentic. Even though the existence of a counterfeit does nothing to refute the existence of the true original, it can still cause us to doubt the Spirit’s testimony in our own hearts. But this is where knowing that these different lines of reasoning all converge on the God of the Bible is helpful. While we typically use these apologetics tools to demonstrate to non-Christians the reasonableness of belief in God and trust in Christ alone, they can also help us to remember the truth ourselves in times of doubtful struggle (or encourage a struggling Christian brother or sister). That gives us multiple supports to lean on when we are weakened by attacks, whether from circumstances without or doubts within. Hence, apologetics helps us to build a resilient faith [2].

[1] See The Blackwell Companion to Natural Theology (Blackwell, 1st edition, 2012) for several of these. See C.S. Lewis, Miracles (Macmillan, 2nd edition, 1960), for his argument from miracles, as well as Craig Keener’s massive 2-volume work on the subject. Also see Chapter 4 of Lewis’ Miracles for his argument from reason, and Ch. 6 in Blackwell for Victor Reppert’s detailed defense of Lewis’ argument from reason and response to objections. Pascal’s “anthropological argument“, presented in chapter 10 of Christian Apologetics, by Doug Groothuis, is another contribution with significant explanatory power.

[2] Though not specifically quoted, much of this last paragraph is inspired by the ever-insightful William Lane Craig, and his excellent book Reasonable Faith, 3rd Ed. (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2008), pp. 43-51 .